Issue 3: The Cuyama Valley

Contributors: Joal Stein, Jack Forinash, Bill Ratzke, Harry Curtis, Ryan Flanagan, Matthew Simeone, Julia Warner, Philip Jankoski, Ellen Freeman and Corbin LaMont.

Photo: Mikola Accuardi

10.75" x 12.75" Broadsheet, Cold Offset Press, Full Color.

Printed by Valley Printers.

Publisher’s Editorial

Written by Corbin LaMont

Edited by Joal Stein, Jack Forinash and Philip Jankoski

Introduction

With Reservation

There is a fifty-mile-long piece of California State Route Highway 166 that runs straight and flat; this is the Cuyama Valley. Mountains on every side, the scenery is dotted with grape vines, small, green rows of crops and dark, black cattle. Heading east you can turn off south onto California State Route Highway 33, a windy piece of road covered in yellow scotch broom taking you through the Los Padres National Forest to the mid-sized hippie town of Ojai. You’ll find yourself traversing the Cuyama Valley if you’re taking Interstate 5 to the Santa Barbara coast or vice versa. Heading from I-5, you’ll dip through some hills, pass the Carrizo Plain National Monument and see a sign that says, “Welcome To The Cuyama Valley,” with smaller text underneath, “Brought to you by The Cuyama Valley Chamber of Commerce.” No such chamber of commerce currently exists, but there is a Cuyama Valley Community Association that meets monthly to discuss and organize around local issues.

The San Andreas Fault runs right through the 206,000 acres of the Carrizo Plain National Monument, which was recently one of many monuments and parks on the political chopping block, threatened with having its current official status downsized. This plain is the largest grassland still protected in the great state of California, thanks in part to the farmers, ranchers, roadside markets, burger joints, and a solar company who signed their support to SaveTheCarrizo.org. With a population of around 3,000 people including Cuyama, New Cuyama, and Ventucopa, this land stretches 300 square miles or 192,000 acres.

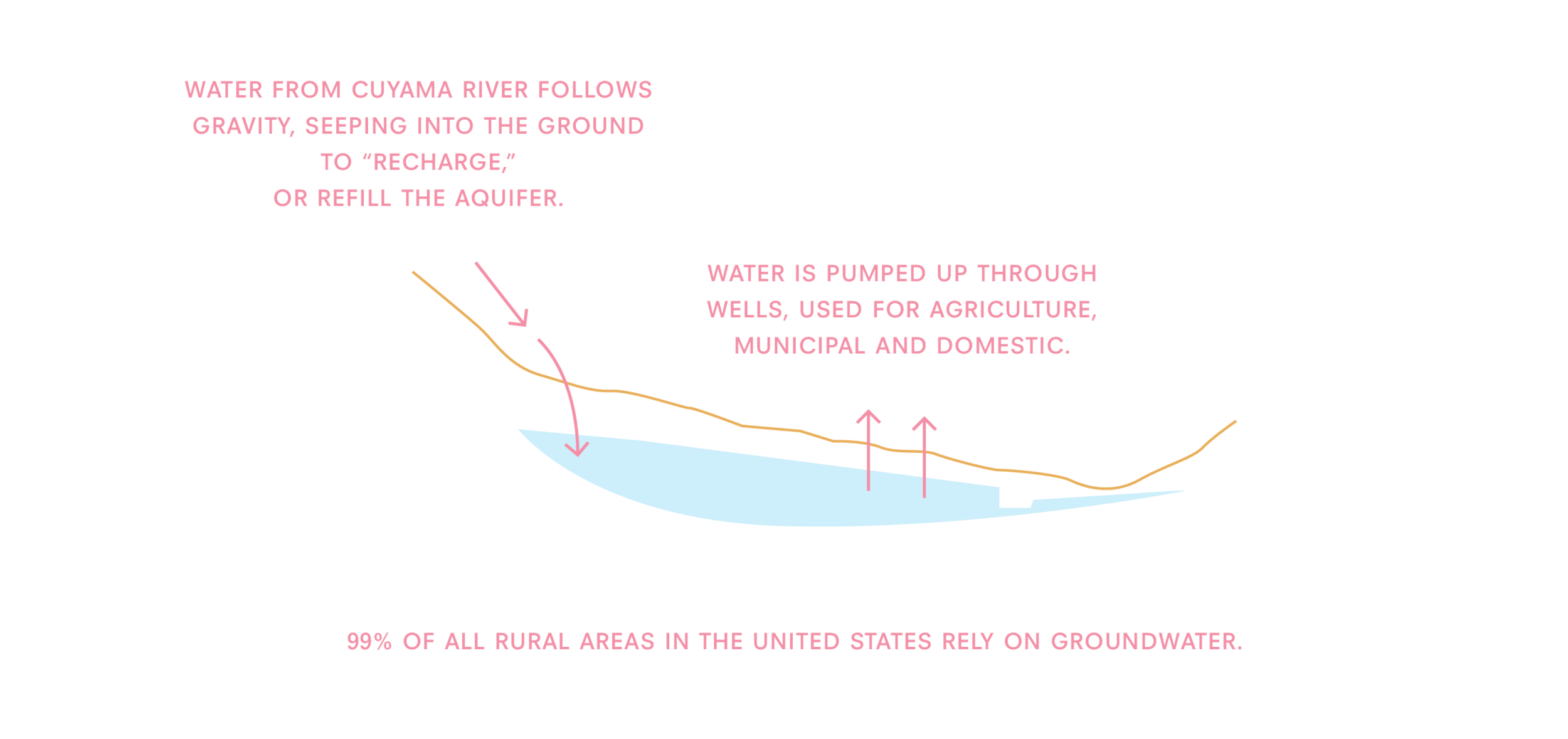

The Cuyama Valley was formed by the runoff of from the surrounding mountains, the Cuyama River a holdover from this long-ago geology is now almost always dry. A desert is created by the protective shadow of the California Coast Ranges. There’s evidence that the Chumash people lived here for 10,000 years, surrounded by antelope, elk, and wildflowers. Just 250 years ago, the Spanish arrived, converting the Chumash to Catholicism, bringing them into the missions, and housing them. In age of Alta California, when the region was under Mexican control, two large plots of land were granted to wealthy Mexican individuals. This type of ownership and organization of land were called rancheros, and even today you can see this spatial organization on a map, rectangular plots neatly arranged. After the Mexican-American War, with the missions closed, the land was given up by Mexico and it became the 31st state of the U.S. The land would be herded, cared for, and quarrelled over for a hundred more years. In the 1940s, drilling began and a new form of crude gold came out of the ground to fuel our heavy steel cars and farm equipment.

There’s a plaque in the townsite of New Cuyama that tells the story of pioneer woman Nancy Kelsey, who went on to sew the first California flag. This plaque sits in the center of a town almost entirely built by Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) in the 1950s. One street was built after 1953, which runs past the community center and The Buckhorn burger joint and sits perpendicular to Highway 166—but it is the exception.

The old ARCO headquarters sits just outside of the townsite, connected to 300 acres of farmland and an airstrip. Advertisements found from New Cuyama’s oil heyday promote “Women from Vegas and Lobster from Mexico.” The airstrip still serves as an attraction but mostly to folks from the region as a good place to land their two-seater planes and walk the half mile over to The Buckhorn for lunch. There’s a dirt and gravel road that runs on the town side of this property. The last street on the grid of New Cuyama’s townsite butts up against the old headquarters so that everyone’s backyards are visible. Cars, patios, storage, kids’ toys, all the elements of living run next to this large piece of formerly corporate land. One side of the road filled to the brim, the other side is a kind of campus created from mowed lawn, scattered buildings, and asphalt.

Today, this headquarters is the home of Blue Sky Center, a nonprofit founded by organic pistachio farmers Gene and Gail Zannon. The Zannon Family Foundation purchased this land in 2012 after it had transferred hands between various idealistic visionaries over the years; as Blue Sky Center it has morphed into a sort of rural incubator where ideas around equitable partnerships, food systems, and community development can be tested and tried. In this latest incarnation of the land, the Zannons initially imagined a small-scale solar power project and sustainable farming that could power social entrepreneurship in this isolated rural community. In conjunction with the ARCO headquarters, Zannon purchased 300 acres of farmland that runs the entire length of the New Cuyama townsite. While some of the farmland is leased, most of it sits fallow, waiting for a vision with a tangible execution.

This sunny, irrigated desert is precarious. History tells us that populations follow economic opportunity. The Chumash people sustained themselves here with the river and plentiful lands. As oil was found in the 20th century the economy of the region was quickly reorganized, and this form of prosperity was pumped out of the ground as quickly as possible. A town was built up and populations were moved here in order to work the wells and provide the necessary labor for resource extraction. Oil reserves and wells began to decline in the late 1960s and ARCO would leave the town it built in 1978. The schools and services they owned would be turned over to the public. A population and culture that had been created for corporate gain would be left behind.

Oddities from this time can be seen in things like all 216 homesites are not individually water-metered, resulting in the town sharing the total water bill each month. Published in December of 2017, the New Cuyama Housing Assessment puts this into perspective: “While housing costs seem relatively low within the context of California, utility costs in New Cuyama are extremely high. Water and sewer services are provided by the Cuyama Community Services District (CCSD), a public entity with high operating costs whose financial burden is divided by the small household population.” Regardless of a New Cuyama household’s size or monthly water usage, their bill will average between $160 to $200 per month.

Although agriculture and ranching existed in this valley for over 200 years, the advent of large-scale agribusiness came to valley by the 1940s, when modern, commodified farming spread all over the United States. The Cuyama Valley saw crop diversification to potatoes, onions, spinach, tomatoes, sugar beets, and carrots. In California, if your land has water under the soil, it’s yours and it’s free! And with plentiful sunshine and free water, why wouldn’t you find a way to grow the most high-yielding, economically-viable crops? This valley is now home to the two largest suppliers of baby carrots, holding 96 percent of the billion-dollar industry. While 21 million gallons of water are being pumped from the Cuyama Valley Groundwater Basin each year, one percent of that is used by the CCSD. With all the water coming out of the ground for industrial agriculture, the town wells are drilling so deep into the ground that the water must be treated in order to be safe for human consumption.

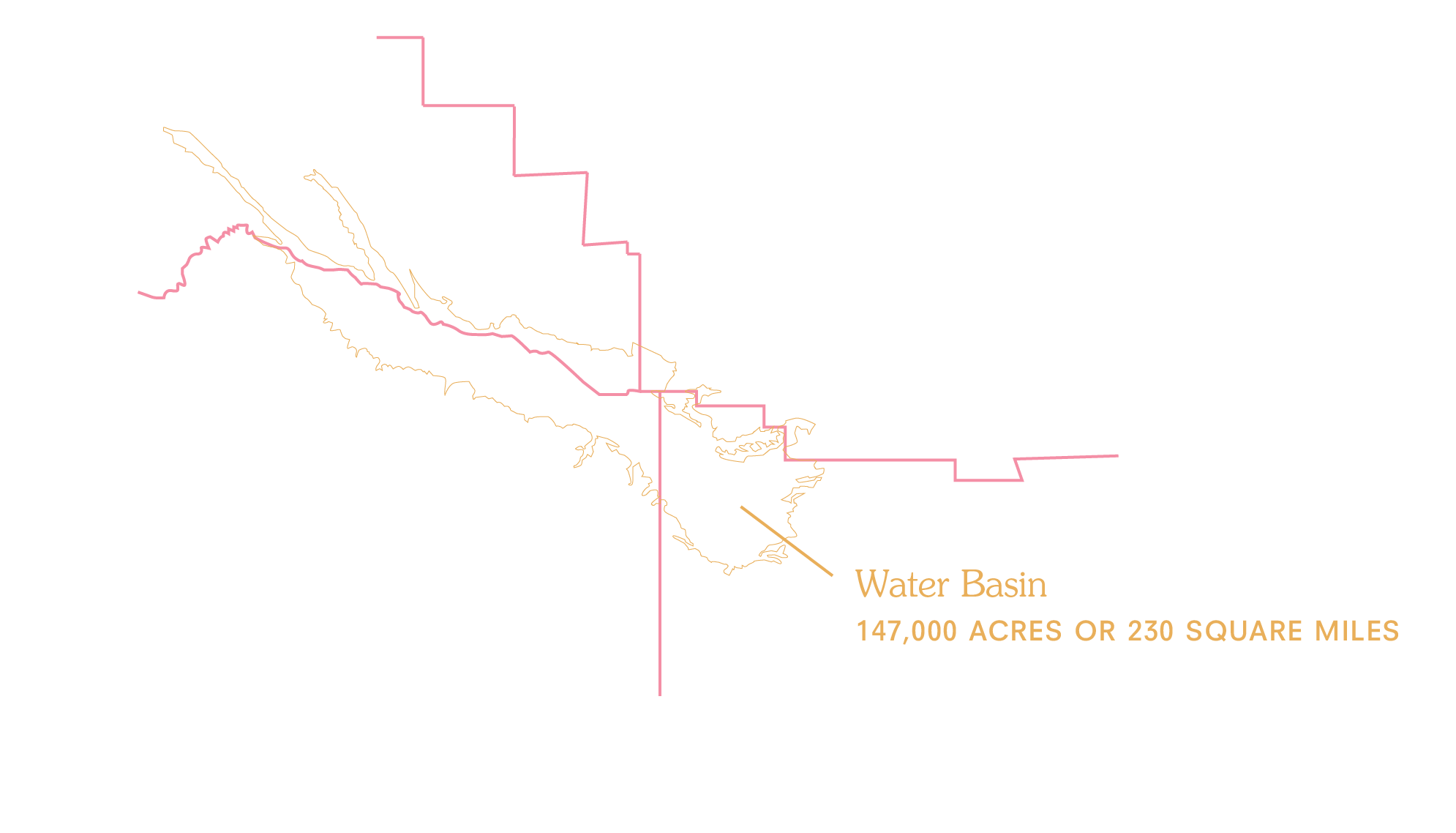

This is an area that crosses through four different counties and has no mayors or city councils, only several different state representatives that oversee the wealthy coastal counties of Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, and Ventura as well as Kern inland. Without larger governing bodies, what this area does have is the Cuyama Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA). In 2014, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act was passed in California, requiring local agencies of each critically overdrafted basin to develop and adopt Groundwater Sustainability Plans by 2010. This legislation demanded that each water district develop a plan and, with no governing body, the Cuyama Groundwater Sustainability Agency was formed to create and administer this plan. Of 21 different critical water basins in the state of California, the Cuyama Valley Groundwater Basin is among the 10 most critical basins.

How long will agriculture be sustainable in this valley at its current rate? According to a recent USGS study of the Cuyama Basin, current extraction is at twice the replenishment rate and the basin has about fifty years of life left at the current levels of pumping. That’s less than two generations until we see a valley decimated by the industries that profited from it. Much of the current population is still being sustained by the dwindling oil industry as well as the agricultural industry. Some members of the New Cuyama townsite have lived in their homes since the purchase of them was subsidized by ARCO. Others have created something out of nothing, from a barren lot to a bustling manufactured home with a handmade stucco porch.

This area continues to be a safe haven for those who want to escape overcrowded or dangerous urban areas. Safety and physical beauty are the primary sources of community pride. But without water, what will sustain in the Cuyama Valley? There’s talk that the town usage is so minor in comparison to industrial agriculture needs that water for this rural population could simply be trucked in. This was tested in December of 2017, when the only town well went down for 12 days due to a mechanical failure which resulted in extreme conservation measures. The Cuyama Community Service District trucked water in from a nearby town to keep up with fire protection standards at the cost of around $40,000. By law communities are required to have a backup well, but today there is only one well; the second town well failed and the newly-drilled replacement was not constructed to governmental standards. The Cuyama Community Service District is working on securing several grants to improve water conditions and capacity. This incident, although temporary, sheds light on the burden this valley faces, which will only be exacerbated over the next fifty years.

All around we hear stories of how farming can’t make money or how it is so incredibly difficult to grow food. The changes in industry and climate have created problems for farmers large and small. Perhaps a telling sign that the Cuyama Valley is connected to California’s Central Valley are signs dotted along the highway that say, “Is Growing Food Wasting Water?.” The mountains create a border between this valley and it’s much larger cousin but they share the same issues. If we could find a solution to managing water in the Cuyama Valley or a way to grow crops that is financially and socially sustainable here, could we take these learnings to 11,520,000 acres of the Central Valley that face the same critical issues?

Accommodations

With Reservation

This region is surrounded by four different mountain ranges. The Carrizo Plain National Monument is an easily accessible way to see the San Andreas Fault ripple to the surface. The sunrises and sunsets challenge that of the popular Joshua Tree National Park. Vast and seemingly sparsely trekked, the Cuyama Valley is glorious.

Just one hour from Santa Barbara and two hours from Los Angeles, people already drive through the valley to recreation areas in and around the Los Padres National Forest. But without a stoplight or even a speed change on the highway, urbanites continue to speed along. If they stop at all, it's for roadside burgers at The Place on Highway 33 or at The Buckhorn in New Cuyama where there’s also a shop to grab some groceries, an antique store called The Junk Jar (open on weekends), and a small town park with a public restroom.

Recently, due to the mudslides in Santa Barbara County, many folks were routed off the coastal highways and through the Cuyama Valley, utilizing I-5 for their various destinations or commutes. Such rare sightings as a ten-person line for the Shell station in Taft had locals lamenting the traffic and “horrible drivers.” It’s clear that one delight of this area is its vacancy.

Is there a balance between buses full of tourists and a more nurturing industry for the land? Could a trail map or recreational guide change the cultural fabric of this place? In the spring of 2017, Alyssa Ravasio, the founder of Hipcamp, an online platform where you can book “over 285,000 campsites, ranches, vineyards, farms, public parks, and more”, visited New Cuyama for an event hosted by Blue Sky Center called The Rural Summit. Ravasio talks about how her desire to create Hipcamp came from seeing public campsites disappear, seeing this need to get people outdoors, and wanting to supply extra income to folks in rural areas.

A very popular Hipcamp site is located right in New Cuyama at Blue Sky Center. An image of it is even on the Hipcamp homepage slideshow, seemingly exemplifying the brand. Some readers might be familiar with the popular Santa Barbara architect, Jeff Shelton, best known for wild tile and metalwork like something out of Dr. Seuss (if Dr. Seuss were in Morocco or Spain—or in his case Santa Barbara). Remember the Zannons, our pistachio farmers with an eye for a better world? They are longtime family friends of Shelton’s. The Shelton Huts were designed and fabricated by Jeff and his daughter, Mattie. They are rustic but whimsical little structures that utilize old farming equipment as the base and have a wonky, covered wagon aesthetic. Totally cute, totally Instagram-worthy, totally cold, just like “real” camping. These huts cost $100/night to rent and made $55,426 last year, making the case for tourism in this valley.

Will urbanites sleeping under a Pendleton blanket save the economy of this valley? More importantly, will they change the culture?

A new artist-in-residency program will be starting at Blue Sky Center in February. Called the 5-5-5—an acronym for five huts, five days, and five artists—this is an opportunity to look at how Blue Sky Center’s momentum will affect the culture of the Cuyama Valley. Each of these artists lives outside the valley and will travel here with their own perspectives. Each of these artists has a community-engaged practice of some kind, a social or public component of their work.

How can these artists magnify or give strength to the existing culture of the Cuyama Valley? In what way will they revive histories that have perhaps been forgotten by the biases of the times?

Some people actively work to change a place for their own self-interest. Others work to change their communities for their own ideas of justice or fairness. Others don’t want a place they think of as just their own to change at all. The inevitable birthing and dying of people creates a generational ebb and flow. Economic and industrial shifts occur rapidly in our modern age. Not everyone wants their places to change, but everyone changes their place.

Application

With Reservation

There is nowhere to stop for a trail map in the Cuyama Valley, no speed limit to slow you down, and no stop sign to make you look. When the preservation of this land and the water of the town is at stake, who will come to its aid? Is there a way to cultivate a more vested interest in area? All of the region’s policymakers live in urban centers away from the reality of their constituents. Does the fact that the major policymakers live in urban areas justify appealing to urban interested in order to maintain local livelihoods? For years urbanites have imported oil, water, and food from rural areas with an “out of sight, out of mind” mentality. Meanwhile people in rural communities visit cities for entertainment, education, and cultural opportunities.

Perhaps we are talking about a reverse cultural flow, where urbanites are coming to rural environments for recreation, outdoor education, and hospitality. Culture is ever-changing and emerging anew, and that can be scary. This is rightfully so, as we often have self-serving or predatory concepts around what is valuable in a social group.

What does tourism look like without a service class?

What does too many visitors feel like?

Attracting qualified teachers to the area has been a longstanding issue for the community. The school owns housing for teachers that come from other places in the area to teach at the local K-12 school district of 240 students. This housing was once used by ARCO to incentivize teachers; the public school district carries this on. One high school teacher travels a harrowing stretch of road over two hours from Ventura to teach in the valley. Some nights he stays in the school district house but he would rather be with his family over the mountain.

There is a large empty grass lot on Highway 166 between Cuyama Valley High School and the rest of the townsite. In the morning and afternoon, silhouettes of teenagers can be seen making their way to and from school on a small dirt path that cuts across it. The parking lot of the CVHS is sparsely used. Outfitted with a shop class, home economics, a sizable garden with fruit trees, and an agricultural studies program, this school has tools at its disposal. Standardized testing, however, rates the high school and elementary school at a 2 (on a scale of 1 being the worst and 10 being the best). Outside of sports, extracurricular programming for teens is very limited.

Could a tourism initiative be led by the young people of the Cuyama Valley?

In Bertie County, North Carolina, high school students conceived, designed, and built a farmstand to serve their rural community. The students were a part of a class created by Emily Pilloton and Matthew Miller where they generated the idea for the project themselves. This was the first project led by their nonprofit Project H, and the farmstand’s success led Emily to give a TED Talk with nearly one million views called “Teaching Design for Change.” The Project H website states that, “To date, the farmers market has retained a thriving community of over 40 vendors, created 4 new businesses, and 15 new full-time jobs.” It’s the kind of hope we want for rural communities all over the nation: produce for a food desert and design/build skills for the next generation.

So, what kind of change are Cuyama Valley teenagers interested in?

The junior class recently held a tamales fundraiser in the cafeteria on a Saturday, advertising with flyers around town. In a performing arts class, students put together a short video piece on the fun of making enchiladas in the classroom. A recent Facebook post on townwide group Cuyama Strong shares, “There's a group of rag-tag kids on sisquoc street selling lemonade for ¢50. If you buy a cup of lemonade, they will give you a free cookie!” Perhaps these young people are interest in taking their enterprises to a broader community.

Could that empty lot that serves as the walking path to school become a laboratory of sorts for tourism and business? Could they build a kiosk, farmstand, retail space, or welcome center? What would they put in a recreation guide for the area? Perhaps they’d want to collaborate with locals on a place to buy products from the area such as olive oil, pistachios, or seasonal produce. Or maybe they’d be more interested in creating their own goods, making their own varietal of pickled carrots or branded tamales.

With 5,250 cars passing by on Highway 166 every day and 48 high school students, what could be dreamed up?